Fast Fashion: Navigating Quality & Ethics in Clothing Purchases

Timeline

Sep 2025 - Nov 2025

Project type

Academic UX research (Master's course)

Role

Principal Investigator, UX Researcher

Methods

Contextual Observation, Semi-structured interviews

Overview

This case study explores how everyday shoppers evaluate clothing quality and ethics when buying fast‑fashion apparel. The project combines contextual observations and semi‑structured interviews to understand not just what people do while shopping, but why they make the choices they do. Moreover, this study was intentionally scoped as research‑only therefore it concludes with a set of actionable opportunity areas and solution directions, but does not move into designing or testing a final product. I served as the principal investigator for this study. My co-researchers and I worked on this project from September to November 2025 as part of a master’s class deliverable. My major contributions includes inductive coding of interview data, report writing (executive summary, discussion), designing interview questions, and leading data analysis through affinity mapping for the observation data, while my teammates and I contributed equally to the overall study.

TL-DR

This research study investigated how consumers evaluate clothing quality, navigate fast-fashion shopping decisions, and consider ethical and sustainability concerns.

We used two user research methods: contextual observations and semi-structured interviews.

Through the observation study, we found that most participants based their purchase decisions primarily on style and price, while many overlooked ethical and sustainability production data. This led us to our key research question: How do consumers navigate the process of purchasing clothing, and in what ways do perceptions of quality and ethical production influence their decisions and behaviors? We designed our interview protocol to explore this research question in depth. Through inductive open coding of interview data, we found key insights: users cared about ethics but struggled to act on these values because transparent sustainability and ethical data was hard to find and difficult to verify; quality is multidimensional, and online reviews and product descriptions covered these aspects only partially and inconsistently. Findings from both methods complemented each other and pointed toward directions for design solutions. These include developing a solution that introduces transparency, credibility, and standardization into the shopping experience, regardless of brand. This would help users make decisions that better align with their values.

The Problem

Fast fashion has fundamentally reshaped how consumers discover, evaluate, and purchase clothing. While rapid production cycles and low-cost items have made fashion more accessible than ever, this accessibility comes at a significant cost. The fashion industry now accounts for approximately 10% of global carbon emissions, generates 92 million tons of textile waste annually, and depends on manufacturing practices that often exploit workers in regions with minimal labor protections and regulatory oversight. What initially sparked this research was a contradiction we saw in our own circles: people often expressed concern about sustainability and guilt about unethical production, yet their actual shopping behavior did not reflect those values. We needed to understand why?

Phase 1: Contextual Observation Study

We started with the observation method to understand the shopping behavior of our participants. This approach gave us a glimpse into what was going on in their minds as they made decisions. How did we go about it? We examined how people make clothing-purchase decisions and how they look for quality or ethics related information. We observed eight participants (three female and five male), recruited through word of mouth and the DePaul College of Computing and Digital Media participant pool. We asked participants to : 1. Visit any clothing retail website of their choice. 2. Select an affordable item they might realistically buy, and attempt to find information about its quality, durability, or ethical production.

Data Synthesis through Affinity Mapping

We collected data from all eight observation sessions in a shared spreadsheet. Then, I collaborated with my team on an affinity-diagramming process to synthesize the data. Each discrete note represented one observable behavior or participant remark and was placed on a digital sticky note, and we collaboratively grouped these notes into clusters that revealed shared patterns. From it emerged 5 themes and they are:

Research Question Refinement - Transitions Phase

The observation phase exposed gaps in our initial framing. Our original question asked how consumers navigate clothing purchases and how quality and ethics shape their decisions, but the data pushed us to refine it to: What structural barriers prevent access to quality and ethics information during shopping, and how do these barriers vary by user motivation? This refinement led to our next phase, where we needed to understand not just what barriers existed but why they mattered differently to different consumers. To uncover those motivations, values, and trade-offs, we designed a complementary semi-structured interview study: observation showed the what, while interviews were intended to reveal the why.

Phase 2: Semi-Structured Interview Study

Semi-structured interviews allowed us to explore individual reasoning, values, and decision-making processes in considerable depth. We recruited six participants representing intentional diversity in shopping motivations and priorities. This diversity of motivation types was essential, as our observation data had suggested that quality definitions and ethics concerns might vary significantly depending on a shopper's primary motivation.

What a Trial Run Taught Us

I led the interview design process, starting with a short protocol of about 5–6 questions, including some warm‑up prompts. Initially, I thought a few broad questions would be enough, but our pilot interview revealed several important gaps. Because the questions were too general, participants gave lengthy answers that touched on multiple topics such as ethics, quality, and sustainability, all at once. This made it difficult to ask deeper follow‑up questions about any specific theme later, since those areas had already been covered. From this, I realized the questions were overlapping and repetitive. To address it, I reorganized the protocol into four focused sections, each dedicated to one topic, and arranged them in a clear, logical sequence - a change that my team also found effective after facing the same issue.

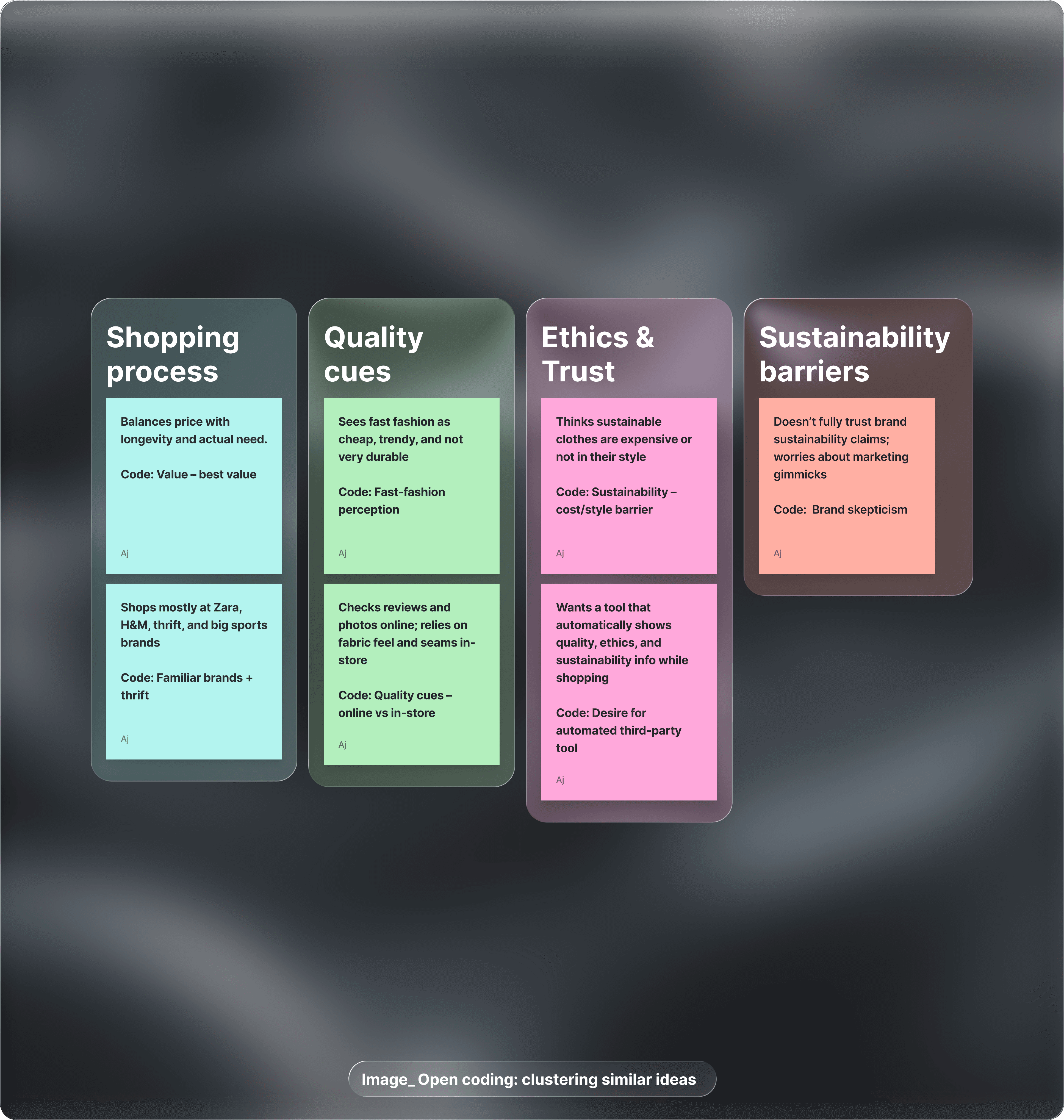

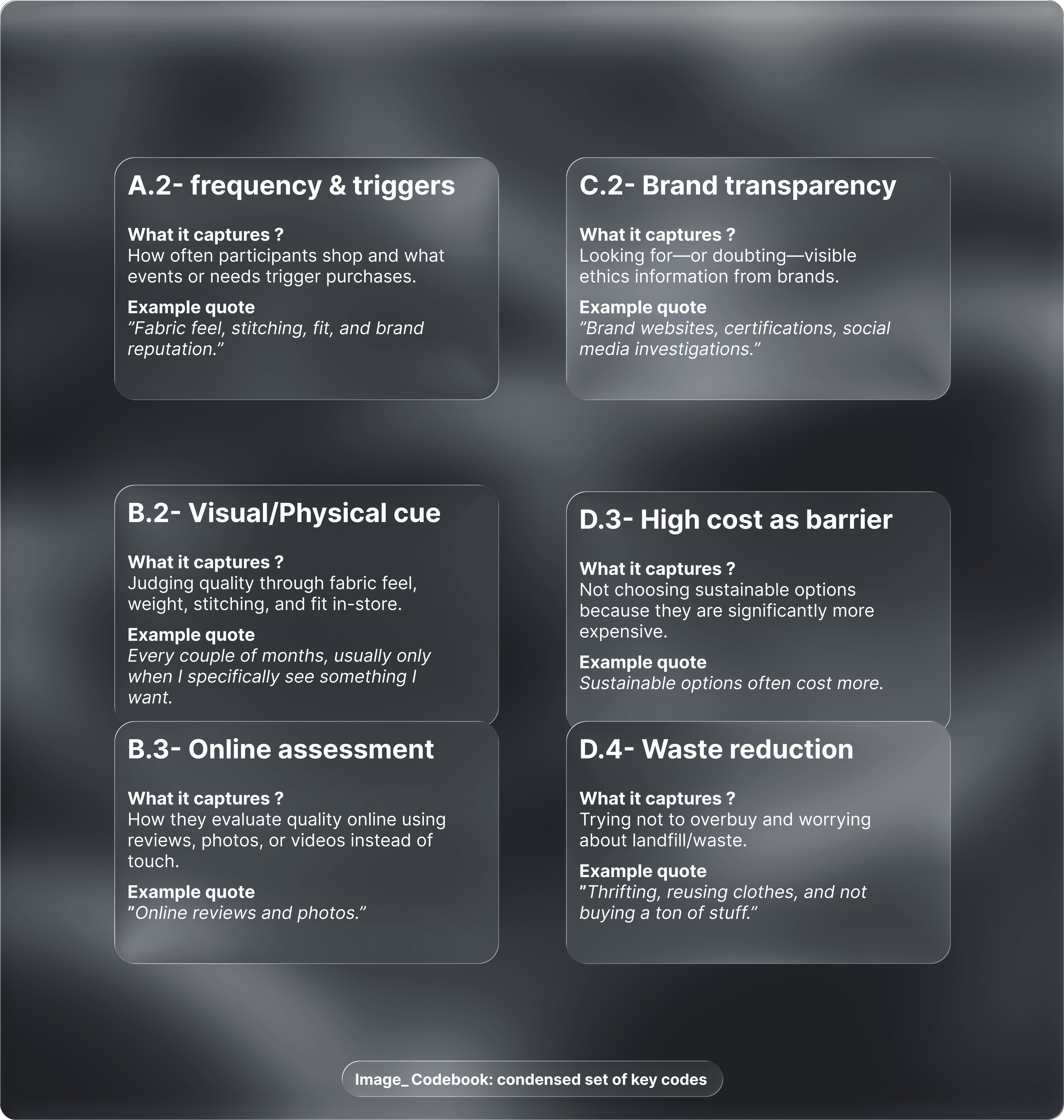

From Interview Responses to Qualitative Analysis

Building on the previous section, which outlined the development of the interview protocol, this phase focuses on its application in the main interview sessions. The protocol yielded rich, detailed responses, and many of the questions raised during the observation and research‑question refinement phases were addressed. The visuals below present selected questions and quotations from the interviews. These excerpts were chosen because they most clearly represent participants’ values, behaviours, and attitudes. Following the interviews, open (inductive) coding was conducted on the transcripts, leading to the development of a structured codebook that informed the subsequent themes and user persona. In this context, open inductive coding involved deriving codes directly from the data, grouping similar segments of text, and allowing patterns to emerge without relying on predefined categories.

Observation and interviews worked together to build a fuller picture of how people shop for fast fashion. Interviews then clarified why these patterns occurred. These combined insights fed directly into three core themes which then informed the evidence‑based persona and subsequent design decisions.

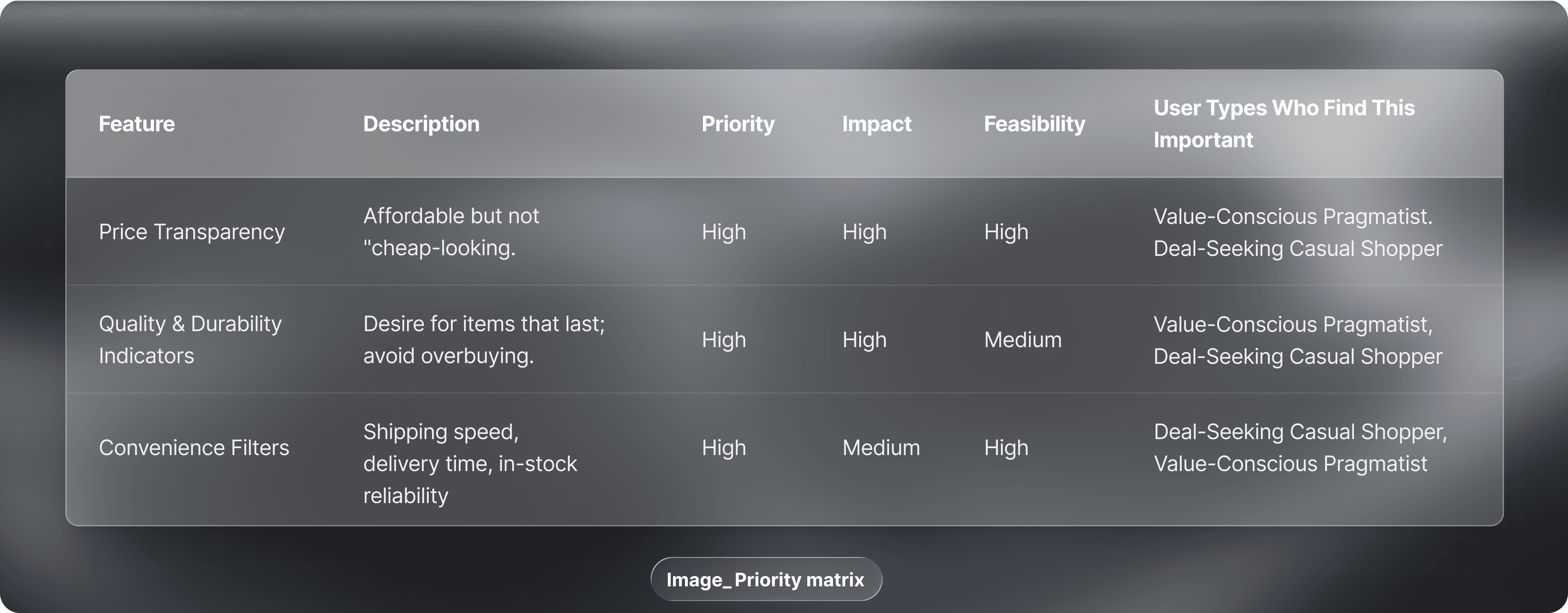

Prioritizing What Matters Most

This matrix ranks the main problems from the themes by impact and feasibility, helping the team decide which user needs to address first.

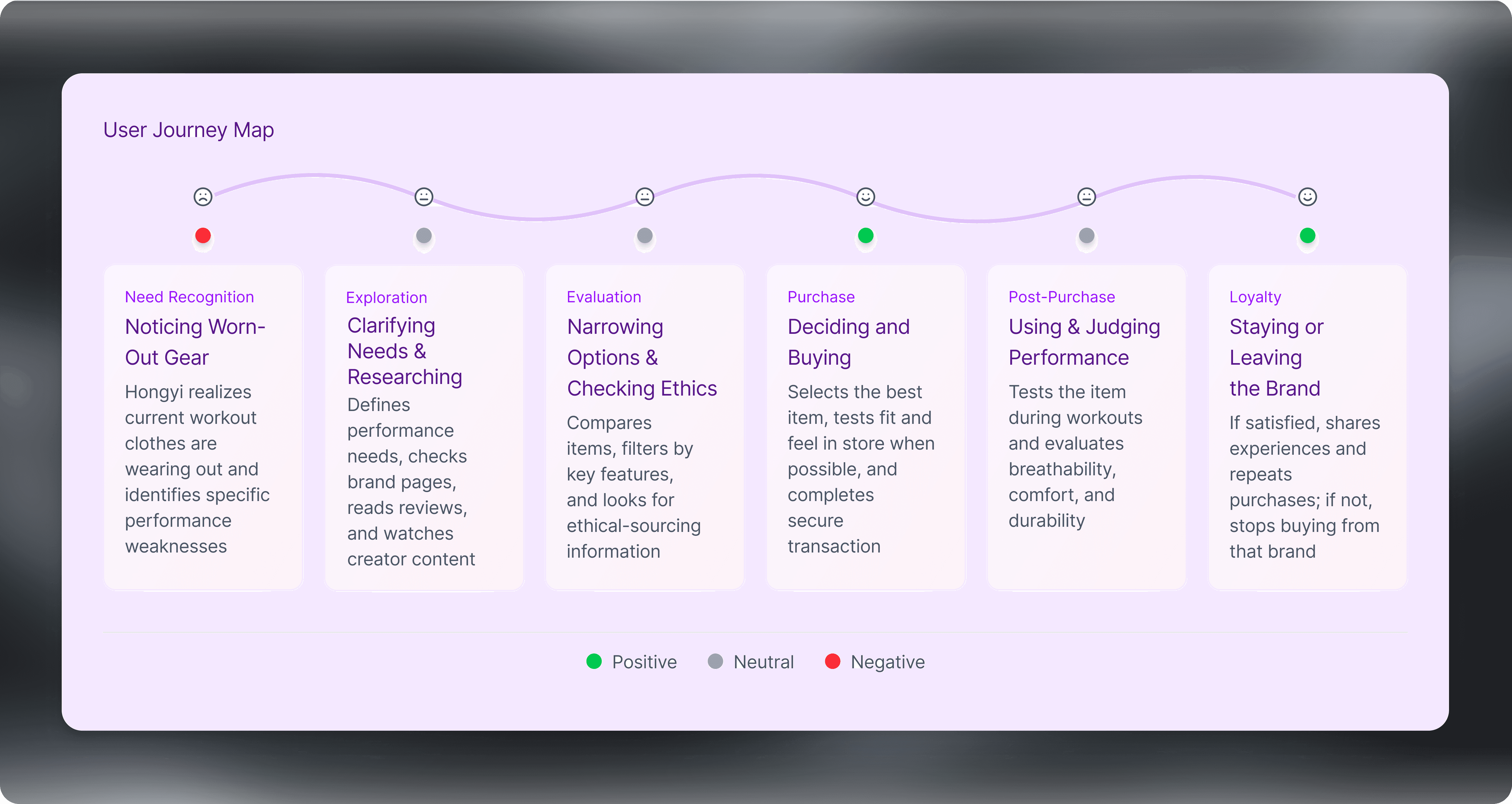

Mapping the User Journey

This journey map shows how the key persona moves through the shopping flow and where pain points from the themes appear along the way.

Bringing It Together in a Persona

This persona synthesizes the research themes into one representative user, making their goals, constraints, and behaviors easy to design for.